The

Mechanisms of the Slippery Slope

Eugene Volokh*

(forthcoming 116 Harv. L. Rev. ___ (2003); Sept. 16,

2002 draft)

I. Introduction............................................................................................................................................................... 2

II. Cost-Lowering

Slippery Slopes and Other Multi-Peaked Preferences Slippery Slopes................................. 11

A. Cost-lowering

slippery slopes....................................................................................................................... 11

B. Cost-lowering

slippery slopes as multi-peaked preferences slippery slopes........................................ 18

C. More

multi-peaked preferences: “Enforcement

need” slippery slopes.................................................. 20

D. Equality

slippery slopes and administration cost slippery slopes.......................................................... 24

E. Multi-peaked

preferences and unconstitutional intermediate positions................................................ 37

F. The

hidden slippery slope risk and unexpected outcomes exposing multi-peaked

preferences........ 38

G. The

hidden slippery slope risk and the ad hominem heuristic................................................................. 40

III. Attitude-Altering

Slippery Slopes.......................................................................................................................... 41

A. Legislative-legislative

and judicial-legislative attitude-altering slippery slopes: The is-ought heuristic, and the normative

power of the actual.......................................................................................................................................................... 41

B. Legislative-judicial

attitude-altering slippery slopes:

“Legislative establishment of policy”............ 45

C. Just

what will people infer from past decisions?........................................................................................ 50

D. Judicial-judicial

attitude-altering slippery slopes and the extension of precedent............................... 59

E. The

attitude-altering slippery slope and extremeness aversion behavioral effects.............................. 61

F. The

erroneous evaluation slippery slope.................................................................................................... 62

G. Are

attitude-altering slippery slopes good or bad?................................................................................... 64

IV. Small

Change Tolerance Slippery Slopes.............................................................................................................. 65

A. Small

change apathy, small change deference, and rational apathy....................................................... 66

B. Small

change tolerance and the desire to avoid seeming extremist or petty.......................................... 69

C. Judicial-judicial

small change tolerance slippery slopes and the extension of precedent................... 71

V. Political

Power Slippery Slopes............................................................................................................................... 73

A. Examples........................................................................................................................................................... 73

B. Types

of political power slippery slopes..................................................................................................... 76

VI. Political

Momentum Slippery Slopes..................................................................................................................... 78

A. Political

momentum and effects on legislators, contributors, activists, and voters.............................. 79

B. Reacting

to the possibility of slippage—the slippery slope inefficiency and the ad

hominem heuristic 83

VII. Implications

and Avenues for Future Research................................................................................................... 84

A. Considering

Slippery Slope Mechanisms in Decisionmaking and Argument Design.......................... 85

B. Thinking

About the Role of Ideological Advocacy Groups.................................................................... 86

C. Fighting

the Slippery Slope Inefficiency..................................................................................................... 88

D. Slippery

Slopes and Precedent...................................................................................................................... 89

E. Empirical

Research: Econometric, Historical, and Psychological............................................................. 89

F. When

(If Ever) Should We Avoid Slippery Slope Reasoning?............................................................... 90

VIII. Conclusion................................................................................................................................................................. 91

“In other countries [than the American colonies], the people . . . judge of an ill principle in government only by an actual grievance; here they anticipate the evil, and judge of the pressure of the grievance by the badness of the principle. They augur misgovernment at a distance and snuff the approach of tyranny in every tainted breeze.”

— Edmund Burke, On Moving His Resolutions for Conciliation

with the Colonies, Speech to Parliament,

I.

Introduction

You are a legislator, a voter, a judge, a commentator, or an advocacy group leader. You need to decide whether to endorse decision A, for instance a partial-birth abortion ban, a limited school choice program, or gun registration.

You think A, on its own, might be a fairly good idea, or at least not a very bad one. But you’re afraid that A might eventually lead other legislators, voters, or judges to support B, which you strongly oppose—for instance, broader abortion restrictions, an across-the-board school choice program, or a total gun ban.

What does it make sense for you to do, given your opposition to B, and given your awareness that others in society might not share your views? Should you heed James Madison’s admonition that “it is proper to take alarm at the first experiment on our liberties,”[1] and firmly oppose something that you might have otherwise supported were it not for your concern about the slippery slope? Or should you accept the immediate benefits of A, and trust that even after A is enacted, B will be avoided?

Slippery slopes are, I will argue, a real cause for concern, as legal thinkers such as Madison, Jackson, Brennan, Harlan, and Black have recognized.[2] And these arguments comport at least partly with our own experience: We can all identify situations where a first step A has led to a later step B that might not have happened without A, though we may disagree about exactly which situations exhibit this quality.[3] A may not logically require B—but for political and psychological reasons, it can help bring B about.[4]

But, as legal thinkers such

as

This need makes many people impatient with slippery slope arguments.[6] The slippery slope argument, the flip response goes, is the claim that “we ought not make a sound decision today, for fear of having to draw a sound distinction tomorrow.”[7] To critics of slippery slope arguments, the arguments themselves sound like a slippery slope: If you accepted this slippery slope argument, then you’d end up accepting the next one and then the next one until you eventually slip down the slope to rejecting all government power (or all change from the status quo), and thus “break down every useful institution of man.”[8] Exactly why, they ask, would accepting, say, a restriction on “ideas we hate” “sooner or later” lead to restrictions on “ideas we cherish”?[9] If the legal system is willing to protect the ideas we cherish today, why wouldn’t it still protect them tomorrow, even if we ban some other ideas in the meanwhile? And of course, even if one thinks slippery slopes are possible, what about cases where the slope seems slippery both ways—where both alternative decisions seem capable of leading to bad consequences in the future?[10]

My aim here is to analyze how we can sensibly evaluate the risk of slippery slopes, a topic that has been surprisingly underinvestigated.[11] I think the most useful definition of slippery slopes is a broad one, which covers all situations where decision A, which you might find appealing, ends up materially increasing the probability that others will bring about decision B, which you oppose.[12] If you are faced with the pragmatic question “Does it make sense for me to support A, given that it might lead others to support B?,” it shouldn’t much matter to you whether A would lead to B through logical mechanisms or psychological ones, through judicial ones or legislative ones, or through a sequence of short steps or one sharp change. Nor should it matter to you whether or not A and B are on a continuum where B is in some sense more of A, a condition that would in any event be hard to define precisely.[13]

The question is whether A might lead to some harmful decisions in the future, through whatever mechanisms. To answer this question, we need to think—without any artificial limitations—about the entire range of possible ways that A can change the conditions (whether those conditions are public attitudes, political alignments, costs and benefits, or what have you) under which others will consider B.

The slippery slope is a familiar label for many of the most common examples of this phenomenon: When someone says “I oppose partial-birth abortion bans because they might lead to broader abortion restrictions,” or “I oppose gun registration because it might lead to gun prohibition,” the common reaction is “That’s a slippery slope argument.” But whatever one calls these arguments, the important point is that the observer is asking the question “Does it make sense for me to support A, given that it might lead others to support B?,” which breaks down into “How much do I like A?,” “How much do I dislike B?,” and, the focus of this article, “How likely is A to lead others to support B?”[14] And this last question in turn requires us to ask “What are the mechanisms through which A can lead others to support B?”

![Text Box:

Camel (A) sticks his nose under the tent (B), which collapses, driving the thin end of the wedge (C) to cause monkey to open floodgates (D), letting water flow down the slippery slope (E) to irrigate acorn (F) which grows into oak (G). [Illustration by Eric Kim, from author’s idea.]](slippery_files/image002.gif)

It is these real-world mechanisms on which I will focus.[15] Slippery slopes, camel’s noses, thin ends of

wedges, floodgates, and acorns are metaphors, not analytical tools. My goal is to describe the real-world paths

that the metaphors represent—to provide a framework for analyzing and

evaluating slippery slope risks by focusing on the concrete means through which

A might possibly cause B.

Specifically, I want to make the following claims, which are closely related but which are worth highlighting separately:

1. Though the metaphor of the slippery slope suggests that there’s one fundamental mechanism through which the slippage happens, there are actually many different ways that decision A can make decision B more likely. Many of these ways have little to do with the mechanisms that people often think of when they hear the phrase “slippery slope”: development by analogy, by decision A changing people’s moral or empirical assumptions about B, or by people becoming “desensitized” to decision B.[16]

To illustrate this briefly, consider the claim that gun registration (A) might lead to gun confiscation (B).[17] Setting aside whether we think this slippery slope is likely—and whether it might actually be desirable—it turns out that the slope might happen through many different mechanisms, or combinations of mechanisms:

- Registration may change people’s attitudes about the propriety of confiscation, by making them view gun possession not as a right but as a privilege that the government grants and therefore may deny.

- Registration may be seen as a small enough change that people will reasonably ignore it (“I’m too busy to worry about little things like this”), but when aggregated with a sequence of other small changes, registration can ultimately lead to confiscation, or something close to it.

- The enactment of registration requirements can create political momentum in favor of gun control supporters, thus making it easier for them to persuade legislators to enact confiscation.

- Non-gun-owners are more likely than gun owners to support confiscation.[18] If registration is onerous enough, over time it may discourage some people from buying guns, thus diminish the fraction of the public that owns guns, diminish the political power of the gun-owner voting bloc, and increase the likelihood that confiscation will be politically feasible.

- Registration may lower the cost of confiscation—since the government would know which people’s houses to search if the residents don’t turn in their guns voluntarily—and thus make confiscation more appealing.

- Registration may trigger the operation of other legal rules that make confiscation easier and thus more cost-effective: When guns aren’t registered, confiscation would be largely unenforceable, since house-to-house searches to find guns would violate the Fourth Amendment; but if guns are registered some years before confiscation is enacted, the registration database might provide probable cause to search the houses of all registered gun owners.[19]

I think that in the registration-to-confiscation scenario, only the latter two mechanisms are fairly plausible; in other scenarios, others may be more plausible. But the important point is that being aware of all these mechanisms can help us as citizens and policymakers think through all the possible implications of some decision A—and can help us as advocates make more concrete and effective arguments for why A would (or would not) lead to B. And even if you are skeptical of one kind of slippery slope claim, you may find that the others are worth considering.

2. As the above example illustrates, slippery slopes are not limited to judicial-judicial ones, where one judicial decision leads to another through the force of traditional judicial precedent. They can also be legislative-legislative, where one legislative decision leads to another (Madison’s concern in his famous Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments[20]), judicial-legislative, and legislative-judicial.

3. Slippery slopes may occur even when a principled distinction could be drawn between decisions A and B. The question isn’t “Can we draw the line between A and B?,”[21] but “Is it likely that other citizens/judges/legislators will draw the line there?”[22]

More broadly, the question ought not be “How should society [or the legal system] decide whether to implement A?” Societies are composed of people who have different views, so one person or group of people may find it worthwhile to oppose A for fear of what others would do if A is accepted. And these others need not constitute all or even most of society—slippery slopes can happen even if A will lead only a significant minority of voters to support B, if that minority is the swing vote.

4. In a stylized world in which voters or legislators are fully rational, have unlimited time to invest in political decisions, and have single-peaked preferences (more on this in Part II.B), slippery slopes turn out to be unlikely. In such a world, if B is unpopular today, it will continue to be unpopular tomorrow, whether or not A is enacted; enacting A therefore won’t cause any slippage to B. Part of the skepticism about slippery slopes may come from the common tendency to assume that we are living in this stylized world, an assumption that is indeed often a sensible first-order approximation.

It turns out, though, that the mechanisms of many slippery slopes are closely connected to phenomena that contradict these simplifying assumptions: bounded rationality, rational ignorance, heuristics that people develop to deal with their bounded rationality, irrational choice behaviors such as context-dependence, and multi-peaked preferences. And since these latter conditions are common in the real world of voters, legislators, and judges, slippery slopes are more likely than one might at first think.

5. Slippery slopes are also connected to path dependence.[23] Once law B has been enacted, it’s often easy to assume that it was predetermined by powerful social forces that no one could have derailed. But path dependence suggests that sometimes a decision A can shift the evolution of a legal rule from one course to another, bringing about a B that would not have otherwise happened. The study of slippery slopes can thus illuminate forms of path dependence that haven’t yet been fully investigated,[24] and the study of path dependence can help illuminate the slippery slope phenomenon.[25]

6. One kind of slippery slope—the attitude-altering slippery slope—is connected to expressive theories of law.[26] “The law,” these theories suggest, “affects behavior by what it says rather than by what it does”;[27] a classic example is bans on smoking in public places helping strengthen a no-smoking-in-public-places norm even when public smoking is rarely legally punished. The attitude-altering slippery slopes would happen when the expressive power of law changes people’s political behavior as well, by leading them to accept new proposals B that they would have rejected before.

7. The existence of the slippery slope creates what I call the slippery slope inefficiency: Decision A may itself be socially beneficial, and many people might agree that it’s beneficial; but the reasonable concern that A will lead to B might prevent the decision from being implemented.[28] One corollary of the inquiry “How likely is A to lead B?” is the inquiry “How can we make it less likely that A will lead to B, so that we can get agreement on A despite some people’s concern about B?” I will propose a few hypotheses along these lines:

- Substantive constitutional rights and limits on government powers can be regulation-enabling, not just regulation-frustrating. A constitutional right to get an abortion, to speak, or to own guns can free people to vote for small (and constitutionally permissible) burdens on the right with less concern that these small steps will lead to broader constraints.[29]

- On the other hand, constitutional equality rights—under the Equal Protection Clause, the Free Speech Clause, or other provisions—are themselves means by which decision A may lead to decision B, if a court concludes that implementing A but then failing to implement B would violate the equality rule.[30] Deferential equality tests, such as the current weak rational basis test applicable to many equal protection claims, thus prevent a particular form of slippery slope.[31]

8. People often evaluate the potential downstream effects of proposals through rules of thumb. Recognizing slippery slope concerns might lead us to change our heuristics;[32] again, here are a few hypotheses:

- People often urge others not to make a big deal out of small burdens: If a new proposal seems to have low costs (to liberty or the public fisc), it should be supported, or at least not strongly opposed, even if it might have low likely benefits.[33] This, for instance, is what many say about modest restrictions on privacy, gun ownership, and other behavior—the restrictions may not offer huge safety benefits, but they aren’t serious restraints on rights, either, so why not try them? Maybe the experiment will pleasantly surprise us, or give us some helpful information about which proposals work and which don’t. And beyond this, fighting this modest experiment might make us seem foolishly intransigent—an argument often levied against abortion rights or gun rights “extremists.”

But the more we believe that the one step now may lead to other steps later, the more we should view such experimentation with concern. We might therefore adopt a rebuttable presumption against even small changes, under which we oppose any proposal A (in certain fields) unless we see it as having really great benefits, because even a seemingly modest restriction has the added cost of increasing the chances of broader restrictions B in the future. And this concern, if it can be persuasively articulated, can provide a response to the “You’re an extremist” argument.

- We are often cautioned against ad hominem arguments, and against impugning our political opponents’ motives, and there is much to these cautions. Nonetheless, the existence of some slippery slope mechanisms may suggest that what one might call an ad hominem heuristic—a policy of presumptively opposing even minor proposals made by certain groups that are also known to support broader proposals, unless the proposal clearly seems to be very good indeed—may be more pragmatically rational than one might think.[34]

9. These heuristics may also shed light on the behavior of advocacy groups such as the ACLU or the NRA. Public consciousness of the possibility of slippage may help prevent the slippage, either by preventing the first steps or by building opposition to the subsequent ones; and one role of advocacy groups is to alert the public to the slippery slope risks, partly by trying to instill the just-mentioned heuristics. This strategy can be dangerous for such groups, because it may make them seem extremist. But, as I discuss throughout and summarize in Part VII.B, such a strategy may be made necessary by the real slippery slope risks that these groups are trying to combat.

10. Thinking about legislative slippery slopes might illuminate two aspects of judicial decisionmaking: reliance on precedent (where judicial-judicial slippery slopes may appear) and deference to the legislature (where legislative-judicial slippery slopes may operate). These parts of the judicial process, it turns out, are closely connected to analogous processes in legislative decisionmaking.[35]

11. Thus, slippery slopes are a real problem, not always but often enough that we cannot lightly ignore the possibility of such slippage. “In the absence of absolute knowledge and consequently absolute control over the consequences of our actions and decisions, we cannot afford to ignore the possible misuses of proposed reforms.”[36]

* * *

The analysis which follows will go through the different kinds of slippery slopes that I have identified (Parts II-VI), illustrating each with a variety of hypotheticals based on real controversies—I hope that readers will find at least some of these illustrations plausible, and will conclude that slippery slopes are possible (even if not certain) in some of these situations.[37] Part VII then briefly summarizes how this analysis might be applied to thinking about ideological advocacy groups, evaluating the likelihood of slippage, crafting slippery slope arguments and counterarguments, avoiding the slippery slope inefficiency, understanding the operation of judicial precedent, and designing future econometric, historical, or psychological research about slippery slopes.

II.

Cost-Lowering

Slippery Slopes and Other Multi-Peaked Preferences Slippery Slopes

A. Cost-lowering slippery slopes

1. An example

Let’s begin with the slippery slope question mentioned in the Introduction: Does it make sense for someone to oppose gun registration (A) because registration might make it likelier that others will enact eventual gun confiscation (B)?[38] A and B are logically distinguishable; but can A help lead to B despite that?

Today, when the government doesn’t know where the guns are, gun confiscation would require searching all homes, which would be very expensive; relying heavily on informers, which may be unpopular; or accepting a probably low compliance rate, which may make the law not worth its potential costs.[39] And searching all homes is expensive both financially and politically, since the searches will annoy many people, including some of the non-gun-owners who might otherwise support a total gun ban.[40]

On the other hand, if guns are registered, a search of all registrants would be both financially and politically cheaper, especially if the law bans one type of gun, covers only a region where they are already fairly uncommon, and perhaps covers only a subset of the population (e.g., public housing residents[41]). Gun registration has been eventually followed by confiscation in England, New York City, and Australia;[42] while it’s impossible to be sure that the registration helped cause confiscation, it seems likely that people’s compliance with the registration requirement made the confiscation easier to implement, and therefore likelier to be enacted. And Handgun Control, Inc. founder Pete Shields openly described registration as a preliminary step to confiscation, though he didn’t describe exactly how the slippery slope mechanism would operate.[43]

Under some conditions, then, legislative decision A may lower the cost of making legislative decision B work, and thus make decision B cost-justified in the decisionmakers’ eyes.[44] There’s no requirement here that A be seen as a precedent, or that A change anybody’s moral or pragmatic attitudes—only that it lower certain costs, here by giving the government information.[45]

2. A diverse preferences explanation for cost-lowering slippery slopes

The cost-lowering slippery slope is driven by voters having a particular mix of preferences; a numerical example might help demonstrate this.

Consider a proposal to put video cameras on street lamps, in order to help deter and solve street crimes. There are obvious limits to this plan, but though it isn’t perfect, it seems promising: Smart criminals will be deterred, and dumb ones will be caught.

And on its own, the plan might not seem that susceptible to police abuse, at least so long as the tapes are recycled, say, every 24 hours, and so long as the cameras aren’t linked to face-recognition software: Under those conditions, the tapes might be effective for fighting low-level street crime, but they wouldn’t make it that easy for the police to track the government’s enemies.[46] People might thus support installing these cameras (decision A), even if they would oppose the use of face-recognition software or the permanent archiving of these tapes (decision B).[47]

But once the legislature implements A, and the government invests money in installing thousands of cameras, in wiring them to the central video recorders or at least to phone lines, and in protecting them from vandals, implementing B becomes much cheaper economically, and thus easier politically. Imagine that, if money were no object, voters would have the following (obviously highly stylized) mix of opinions:

· 20% of the public would oppose even decision A, because they don’t want the police videotaping street activity at all;

· 20% of the public would support A but oppose B, because they like videotaping only if tapes are quickly recycled and no face recognition software is used;

· 60% of the public would support B, because they like police videotaping more generally, and would certainly support A if that’s all they can get.

But imagine that 30% of the second and third groups would nonetheless oppose decisions A and B because they cost too much. The mix of preferences would thus be:

|

# |

Preference |

Would support in principle and given the cost (e.g., if there are no cameras yet, and we’re in position 0) |

Would support in principle, if there were no extra cost (e.g., if there are already cameras up, because A was already implemented) |

|

1 |

0: no cameras |

20% |

20% |

|

2 |

A: cameras, no face recognition and no archiving |

14% |

20% |

|

3 |

B: cameras, with face recognition and archiving |

42% |

60% |

If the people in group 2 focus only on the vote on A, those of them who don’t mind the financial cost would vote “yes”; and with group 2’s 20% ´ 70% + group 3’s 60% ´ 70% = 56% of the vote, A would get enacted.[48] But a few years later, when someone suggests a switch to B at no extra cost, that proposal would also be enacted, since 60% of the public would now support it, given that there’s no more fiscal objection.

Thus, the group 2 people must make a tough choice: Do they like A so much that they’re willing to accept the risk of B as well, or are they so concerned about B that they’re willing to reject A? The one item that is off the table is the one group 2 most prefers, which is A alone. The cost-lowering slippery slope has eliminated that possibility, at least unless there’s a constitutional barrier to B, or unless the government can somehow set up special cameras that would be very expensive to convert to mode B.

3. Cost-lowering slippery slopes, the costs of uncertainty, and learning curves

The above example involves the cost of tangible material—cameras. But another cost of any new project is the cost of learning how to properly implement it, and the related risk that it will be implemented badly.

Many new proposals, from social security privatization to education reform are viewed skeptically on these very grounds, at least by some. Broad change B—for instance, an across-the-board school choice program—might thus be opposed by a coalition of (1) people who oppose it in principle (for instance, because they don’t want tax money going to religious education, or because they want to maintain the primacy of government-run schools), and (2) those who might support it in theory but suspect that it would be badly implemented in practice.[49] This lineup is similar to what we saw in the camera example.

But say that someone proposes a relatively modest school choice program A, for instance one that is limited to nonreligious schools, or to children who would otherwise go to the worst of the government-run schools.[50] Some people might support this project, because it has value on its own. But as a side effect of A, people will learn how school choice programs can be properly implemented, for instance what sorts of private schools should be eligible, how (if at all) they should be supervised, and so on.

If A is a total failure, then voters may become even more skeptical about the broader proposal B. But if after some years of difficulty, the government eventually creates an A that works fairly well, some voters might become more confident that the government—armed with this new knowledge derived from the A experiment—can implement B more effectively.

A will thus have led to a B that, were it not for A, might have been avoided. In the path dependence literature, this is described as a form of “increasing returns path dependence” that focuses on “learning effects”: “In processes that exhibit . . . characteristics [such as learning effects], a step in one direction decreases the cost (or increases the benefit) of an additional step in the same direction, creating a powerful cycle of self-reinforcing activity or positive feedback.”[51] And because of this increasing returns path dependence, “decisions may have large, unanticipated, and unintended effects.”[52]

For those who support broad school choice (B) in principle, this is good: The experiment with A will have led some voters to have more confidence that B would be properly implemented, and thus made enacting B more politically feasible.

But, as with the cameras example, those who support A but oppose B in principle might find that their voting for A has backfired. Some of A’s supporters might therefore decide to vote strategically against A, given the risk that A would lead to B. The government, they might reason, ought not know how to efficiently do bad things like B (bad in the strategic voter’s opinion), precisely because the knowledge can make it likelier that the government will indeed do these bad things.

4. Legal-cost-lowering slippery slopes

Let us return briefly to the “gun registration may increase the chances of gun confiscation” argument. Today, gun confiscation would be hard to enforce, among other things because of the Fourth Amendment.[53] Searching all houses for some or all kinds of guns would today be unconstitutional, close to the paradigm of an impermissible general search.[54] This is in a sense a cost of confiscation—not a financial cost, but a legal cost that keeps confiscation from being performed efficiently.[55]

If, however, guns are successfully registered, a house-to-house search of registered owners’ homes may well become constitutional. Your registration as the owner of a weapon may be seen as creating probable cause to believe that you have it; and one place you’re likely to keep it is your home. This isn’t a certainty—maybe the gun was stolen or lost, and you didn’t report this to the police, or maybe you’re keeping the gun in some other location—but a magistrate may find that it suffices for probable cause, and issue a search warrant that would let the police search your house for the gun.[56]

Gun registration (legislative decision A) thus leads to some degree of public compliance with the registration requirement. This compliance has the legally significant effect of creating probable cause to search all registrants’ houses, once guns are banned. This legally significant effect makes it easier to enforce the gun ban—and thus makes it likelier that such a ban will be enacted (legislative decision B).

Again, this scenario doesn’t require us to assume that registration will be seen as morally indistinguishable from confiscation, or that registration will set a precedent, or that registration will desensitize voters to confiscation. Decision A can make B likelier even if it doesn’t change a single voter’s, legislator’s, or judge’s mind about the moral propriety of gun prohibition or confiscation. Rather, the legally significant effect of registration can change the practical cost-benefit calculus surrounding prohibition, and thus make prohibition more likely (though of course not certain).[57]

5. Being alert to the risk of cost-lowering slippery slopes

This suggests that decisionmakers—legislators, voters, advocacy groups, or opinion leaders deciding whether to oppose a particular proposals—should consider how a government action would change the costs of implementing future actions, in particular:

· How would this government action provide more information to the government (e.g., who owns the guns), and what other actions (e.g., seizing the guns) would be made materially cheaper by the availability of this information?

· How would this government action provide more tools to the government (e.g., video cameras), and what other actions (e.g., automated face recognition, videotape archiving) would be made cheaper by the existence of these tools?[58]

·

How would

this government action provide more

experience to the government in doing certain things, and what other

actions would this extra experience make less risky and thus more politically

appealing?

·

How would this government action provide more legal power to the government

(e.g., the power to search people’s homes), and what other actions would this

extra grant of power make possible or make easier?

Opponents of B can’t

simply console themselves with the possibility that a reasonable line between A

and B can logically be drawn, to

dismiss the slippery slope concern as being that “we ought not make a sound decision today, for fear of having to draw a

sound distinction tomorrow,”[59]

or to argue that

Someone who trusts in the checks and balances of a democratic society in which he lives usually will also have confidence in the possibility to correct future developments. If we can stop now, we will be able to stop in the future as well, when necessary; therefore, we need not stop here yet.[60]

There’s a different “we” involved: Those who support A but oppose B should fear that if they vote for A now, such a vote may lead others to vote for B later—and that though a logical line could be drawn between A and B (yes cameras, no archiving, no face recognition), most voters will decide to draw the line on the far side of B rather than on the near side. Even those who generally trust that their society is democratic can thus rationally oppose a decision that they like on its own, for fear that it will lower the cost of another decision that they dislike, and thus make that decision more likely.

6. Constitutional rights as tools for preventing the slippery slope inefficiency

The examples above illustrate the Slippery Slope Inefficiency: Even if a majority of voters believe decision A (e.g., gun registration) is good policy on its own, A may be rejected because enough of those voters fear that A will lead to B (gun prohibition), which they oppose.[61] And the examples point to one possible way of preventing the inefficiency—courts recognizing constitutional rights that would prevent B, such as a non-absolute right to own guns.[62] Once this constitutional precommitment makes B much less likely, opponents of B thus have less to fear (to the extent they trust the courts) and can thus support A, or at least oppose it less.

Constitutional constraints are thus not only legislation-frustrating (because they prohibit total bans on guns) but also in some measure legislation-facilitating (because some voters may support more modest gun controls, once they stop worrying that these controls will lead to a total ban). Changing a constitution to secure a right may thus sometimes be good both for some who want to moderately protect the right and for some who want to moderately restrict it—though naturally much depends on how broad the right would be, and on what political power the various groups have.[63]

B. Cost-lowering slippery slopes as multi-peaked preferences slippery slopes

Cost-lowering slippery slopes, it turns out, are a special case of a broader mechanism—the multi-peaked preferences slippery slope.

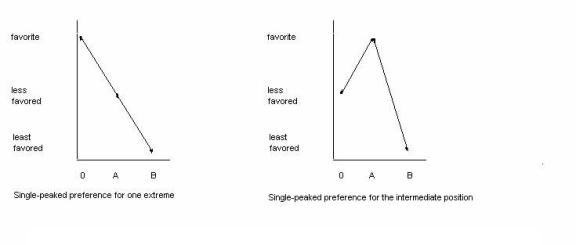

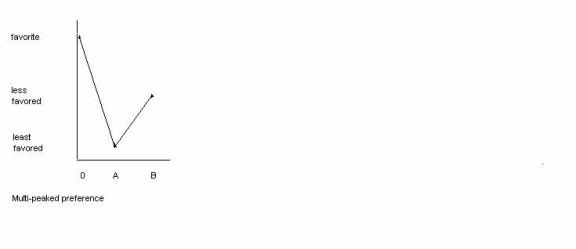

In many debates, one can roughly divide the public into three groups: traditionalists, who don’t want to change the law (they like position 0), moderates, who want to shift a bit to position A, and radicals, who want to go all the way to position B. What’s more, one can assume “single-peaked preferences”:[64] Both traditionalists and radicals would rather have A than the extreme on the other side. We can represent the preferences the following way, which is why the preferences are called “single-peaked”:

If neither the traditionalists nor the radicals are a majority, the moderates have the swing vote, and thus needn’t worry much about the slippery slope. Say that 30% of voters want no street-corner cameras (0), 40% want cameras but no archiving and face recognition (A), and 30% want archiving and face recognition (B). The moderates can join the radicals to go from 0 to A; and then they can join the traditionalists to stay at A instead of going to B. So long as people’s attitudes stay fixed, there’s no slippery slope risk:[65] Those who prefer A can vote for it with little risk that A will enable B.

But say instead that some people would prefer 0 best of all (they’d rather have no cameras, because they think installing cameras costs too much), but once cameras are installed they would think that position B (archiving and face recognition) is better than A (no archiving and no face recognition): “If we spend the money for the cameras,” they reason, “we might as well get the most bang for the buck.” This is a multi-peaked preference—these people like A least of all, preferring either extreme over the middle.

Let’s also say that shifting the law from one position to another requires a mild supermajority, say 55%; a mere 50%+1 vote isn’t enough, because the system has built-in brakes (such as the requirement that the law be passed by both houses of the legislature, the requirement of an executive signature, or a more general bias in favor of the status quo).[66] We can thus imagine the public (or the legislature) split into several different groups, each with its own policy preferences and its own voting strength.

|

Group |

Most prefers |

Next preference |

Most dislikes |

Attitude |

Voting Strength |

|

1 |

0 |

A |

B |

“As little surveillance as possible, either (1) as a

matter of principle, or (2) because we prefer surveillance level A as a

matter of principle, but think cameras are too expensive” |

26% (20% for (1) + 6% for (2)) |

|

2 |

0 |

B |

A |

“Cameras are too expensive, but if the money is spent,

might as well get as much surveillance for it as possible” |

18% |

|

3 |

A |

0 |

B |

“We prefer moderate surveillance level A, and

definitely no more” |

14% |

|

4 |

A |

B |

0 |

“We prefer surveillance level A, and definitely no

less” |

0% (in this example) |

|

5 |

B |

0 |

A |

“We want maximum surveillance, but if we can’t have

that, we’d rather have no surveillance instead of A” |

0% |

|

6 |

B |

A |

0 |

“We want maximum surveillance, and cost isn’t a

concern” |

42% |

This is exactly the same preference breakdown as in the simpler table on p. 13; and, as in that table, the direct 0®B move fails, because it gets only 42% of the vote (group 6), but the 0®A move succeeds with 56% of the vote (groups 3 and 6) and then the A®B move succeeds with 60% of the vote (groups 2 and 6).[67] And, as before, members of group 3 must now regret their original vote for the 0®A move, because that vote helped bring about result B, which they most oppose.

Multi-peaked preferences thus make the moderate position A politically unstable—which means that implementing A can grease the slope for a B that would otherwise have been blocked.

C. More multi-peaked preferences: “Enforcement need” slippery slopes

“As first and moderate methods to attain unity have failed, those bent on

its accomplishment must resort to an ever-increasing severity. . . . . Those who begin coercive elimination of

dissent soon find themselves exterminating dissenters. . . . [T]he First Amendment to our Constitution was

designed to avoid these ends by avoiding these beginnings.”

— West Va. State Bd. of Ed. v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624 (1943) (Jackson, J.).

There are many possible multi-peaked preferences slippery slopes besides the cost-lowering slippery slope; one example is the enforcement need slippery slope.

Imagine marijuana is legal, and the question is whether to ban it. Some prefer to keep it legal (0), others want to ban it but enforce the law mildly (A), and others want to ban it and enforce the law severely, with intrusive searches and strict penalties (B).

But say also that some people would prefer 0 best of all (they’d rather keep marijuana legal), but once marijuana is outlawed they would think that position B (strict enforcement) is better than A (lenient enforcement). “Laws should be enforced,” they might argue, “because not enforcing them only teaches people that law was meaningless and that they can violate all sorts of laws with impunity.” Obviously, if they thought the law is extremely bad, they would have preferred that it be flouted with impunity than have it be strictly enforced. But let’s assume they think the law is only slightly unwise, whereas leaving such a law unenforced is very unwise.[68] We again see a multi-peaked preference—people like A least, preferring either extreme over the middle.

Let’s assume, as before, that it takes at least a 55% supermajority to shift from the status quo,[69] and let’s assume that the group breakdown is as follows:

|

Group |

Most prefers |

Next preference |

Most dislikes |

Attitude |

Voting Strength |

|

1 |

0 |

A |

B |

“Restrict drugs as little as possible” |

10% |

|

2 |

0 |

B |

A |

“Restricting drugs is bad, but contempt for the law

is even worse” |

20% |

|

3 |

A |

0 |

B |

“A little restriction is good, but hard-core

enforcement is very bad” |

20% |

|

4 |

A |

B |

0 |

“A little restriction is good, and having no

restriction is very bad” |

10% |

|

5 |

B |

0 |

A |

“Drugs are bad, but contempt for the law is even

worse” |

10% |

|

6 |

B |

A |

0 |

“Drugs are bad, do as much as you can to stop them” |

30% |

Given these preferences, a proposal to shift from position 0 (marijuana legal) to B (a sternly enforced marijuana ban) would fail: It would get the votes of groups 4, 5, and 6, only 50%. But a proposed 0®A shift (to a weakly enforced ban) would succeed, with a 60% supermajority coming from groups 3, 4, and 6. Once A is enacted, then a proposed A®B shift would also succeed, with the votes of groups 2, 5, and 6, also 60%. And then shifting from B back to 0 would be impossible, since such a proposal would only get the votes of groups 1, 2, and 3, just 50%.[70]

Decision A wouldn’t change anyone’s underlying attitudes; rather, it would lead one small but important swing group (the 20% of the voters in group 2) to vote for B, based on their preexisting preference for B over A, even though the group would have opposed B had the status quo remained at 0.[71] Even when only a minority of voters (30%, groups 2 and 5) exhibit multi-peaked preferences, and an even smaller minority take the enforcement need view that “we don’t much like the law but we dislike people flouting the law even more” (20%, group 2), A can cause slippage to B.[72]

The lesson, then, is for the moderates in group 3, who like A but worry that their supporting A would eventually help bring about B, which they dislike. They should ask themselves: “What fraction of our anti-B coalition will start backing B if we enact A?” If the answer looks high enough (as it is in this hypothetical), that might be reason for group 3 members to resist the original move to A, even if they like A on its own.[73]

This analysis suggests that when people consider a proposal A, they should also think systematically about

· what enforcement problems might arise after A is enacted,

· what proposal B might become more popular as means of fighting these enforcement problems,

· whether B would be harmful enough and likely enough that the danger of B being enacted justifies opposing A in the first place, and

· whether there’s some way of minimizing the risks that B will come about, perhaps by coupling A with some up-front assurances that B will be rejected.

Unfortunately, though these points aren’t rocket science, we often don’t think about them in an organized way. Consider an example stemming from an article I wrote defending red-light enforcement cameras.[74] The cameras photograph the front license plate and the driver’s seat of cars that enter intersections on red, and enforcement authorities then mail a ticket to the car’s registered owner. The owner can fight the ticket either by showing up in court, where the judge can see that the owner wasn’t the photographed driver, or by telling the court in writing who the actual driver was. My article reasoned that this proposal (A) was a good idea, for various reasons.

Unfortunately, I neglected to consider the enforcement need slippery slope. As some readers pointed out, A might lead some drivers to wear mild disguises—floppy hats, headscarves, large sunglasses—that conceal their identities. When the camera photographs these drivers, the photos probably wouldn’t provide enough evidence that they were actually driving, and this may let them evade the ticket.

This may cause substantial political pressure to go on to step B, where the law is changed to impose liability on the car’s owner, whose identity is disclosed by the license plate, rather than on the driver.[75] In the pre-A world, such an owner liability proposal may arouse opposition, because many people might think it unfair for the owner to be punished for another’s wrongdoing. But once A is enacted, people’s tendency to want to punish scofflaws, coupled with a desire for evenhanded enforcement, may persuade some fraction of the public to support B; and that fraction may be enough of a swing vote to get B enacted.

In my view, result B isn’t bad,[76] but others might disagree, because they strongly oppose vicarious liability systems such as B. Had I thought systematically about enforcement need slippery slopes, my article could have alerted readers to this risk that A will lead to B, and might have anticipated and deflected some possible objections to B.

And thinking ahead about these slippery slope risks might also let opponents of owner liability (B) find ways to implement red-light cameras (A) while decreasing the chance that B will happen. For instance, supporters of red-light cameras and opponents of owner liability might make a legislative deal, in which the law allowing red-light cameras explicitly prohibits owner liability—the deal won’t be legally binding on future legislatures, but it might have at least some moral or political influence on the lawmakers, thus making B somewhat less likely.

D. Equality slippery slopes and administration cost slippery slopes

1. The basic equality slippery slope

Multi-peaked slippery slopes can happen when a significant group of people prefers both extremes to the compromise position. One such situation is when A without B seems unfairly discriminatory. Consider the following example:

· Position 0 is no school choice—the state funds only public schools.

· Position A is secular school choice—the state funds public schools but also gives parents a voucher that they can take to private secular schools but not to religious schools.

· Position B is total school choice—the state funds public schools but also gives parents a voucher that they can take to any private school, secular or religious.

And let’s say that voters break down just as in the previous example:

|

Group |

Most prefers |

Next preference |

Most dislikes |

Attitude |

Voting Strength |

|

1 |

0 |

A |

B |

“As little school choice as possible” |

10% |

|

2 |

0 |

B |

A |

“No school choice is best, but better total school

choice than discriminatory exclusion of religious schools” |

20% |

|

3 |

A |

0 |

B |

“Secular school choice is better than none, but

definitely no inclusion of religious schools” |

20% |

|

4 |

A |

B |

0 |

“Secular school choice is best, but we can live with

including religious schools” |

10% |

|

5 |

B |

0 |

A |

“Total school choice is best, but better no school

choice than discriminatory exclusion of religious schools” |

10% |

|

6 |

B |

A |

0 |

“As much school choice as possible” |

30% |

Because 30% of the people (groups 2 and 5) have multi-peaked preferences driven by their hostility to discrimination between private religious schools and private secular schools, there is an equality slippery slope. Total school choice would only have gotten 50% (groups 4, 5, and 6) if it had been proposed without the intermediate step of secular school choice. But proceeding one step at a time, we have a 60% vote for secular school choice (groups 3, 4, and 6), and then a 60% vote for total school choice (groups 2, 5, and 6), driven largely by group 2’s strongly preferring equality.

Once this happens, and the system has gone all the way to total school choice, group 3 must regret its original support for A (secular school choice). Total school choice is the worst option from group 3’s perspective, and yet it was group 3’s support for the halfway step of secular school choice that made total school choice possible.[77]

This example illustrates that an equality slippery slope can happen without A and B being indistinguishable. Here, a majority of voters concludes that A and B needn’t be treated equally; but the slippage happens because a minority (here, 30%) exhibits a multi-peaked preference by preferring either form of equal treatment (0 or B) to unequal treatment (A).[78] Thus, even those who support A on its own, and who firmly believe that A and B can be logically distinguished, might be wise to oppose A if there’s enough risk that implementing A will lead others to also end up supporting B.

Equality slippery slopes are made particularly likely by equality being such an appealing norm. Consider for instance the assisted suicide debates, where allowing “those in the final stages of terminal illness who are on life support systems . . . to hasten their deaths by directing the removal of such systems” (A) has led to arguments that it’s wrong for “those who are similarly situated, except for the previous attachment of life sustaining equipment, [to be] not allowed to hasten death by self administering prescribed drugs” (B).[79] Even people who might be hesitant about B at first (though probably not those who bitterly oppose B) might also be reluctant, once A is allowed, to deny to some of the dying a release that is offered to others. The acceptance of A may thus increase the chances that B may take place, even if A’s supporters had sincerely insisted that they were only seeking A and not B.

Likewise, one might reasonably worry that once B (assisted suicide for the terminally ill) was implemented, people’s equality concerns would push them to allow assisted suicide for still more people (C), such as the “chronically ill, who have longer to suffer than the terminally ill, or . . . individuals who have psychological pain not associated with physical disease”—”[t]o refuse assisted suicide or euthanasia to these individuals would be a form of discrimination.”[80] This is especially so because there are concrete claimants here asserting their right to be treated equally. Even if courts can roughly distinguish category B from category A in a way that’s sensible in general, though arbitrary in close cases, judges may be reluctant to apply this distinction to a real person whose particular close case they are deciding.

This sort of equality-based slippage has indeed happened in the Netherlands. Dutch courts began by declining to punish doctors who assist the suicides of the terminally ill. They then extended this to those who are subject to “unbearable suffering,” without any requirement that they be terminally ill.[81] They then extended this to a person who was in seemingly irremediable mental pain, caused by chronic depression, alcohol abuse, and drug abuse, on the theory that the suffering of the mentally ill is “experienced as unbearable” by them, presumably comparably to how the physically ill experience physical suffering.[82] Dutch courts then extended this to a 50-year-old woman who was in seemingly irremediable mental pain caused by the death of her two sons, again on the theory that “[h]er suffering was intolerable to her.”[83] “Intolerable psychological suffering is no different from intolerable physical suffering,” the doctor in that case reasoned, and the court agreed, concluding that “the source of the suffering [was] irrelevan[t].”[84]

In these examples, the bottom of the equality slippery slope is more government funding or more freedom from restraint, but the slope could also lead towards greater government power and greater restrictions. For instance, when one free speech exception is created for one constituency, others may resent even more the absence of an exception for their own favored cause.

Consider one argument in favor of campus speech codes:

Powerful actors like government agencies, the writers’ lobby, industries, and so on have always been successful at coining free speech ‘exceptions’ to suit their interest—copyright, false advertising, words of threat, defamation, libel, plagiarism, words of monopoly, and many others. But the strength of the interest behind these exceptions seems no less than that of a black undergraduate subjected to vicious abuse while walking late at night . . . .[85]

Or consider the similar argument that the existence of the obscenity exception should justify bans on Nazi advocacy because “There is no principled reason to permit the banning of material that appeals to a depraved interest in sex but not the banning of material that appeals to a depraved interest in violence and mass murder.”[86]

Some people who make such arguments might have supported decision B (creating a new free speech exception) even had decision A (the creation of the old free speech exceptions) never been made. But their making the equality argument suggests that they think some listeners might be moved by the analogy between A and B.[87] This attitude may be characterized as a worthy love of equality or consistency, or as unworthy “censorship envy”[88]—but in either case it is a real phenomenon.[89] So far, U.S. courts have resisted these arguments, but U.S. political leaders,[90] future U.S. courts,[91] and politicians and courts in other countries that have a narrower view of free speech may well find them logically and emotionally appealing.[92]

2. Administration cost slippery slopes

An intermediate position A might also be untenable if it’s burdensome to administer. One obvious burden might be the effort required to make and then review decisions under a nuanced, fact-intensive rule: For instance, the Court came within one vote of slipping—for better or worse—down the slope to entirely eliminating the obscenity exception, partly because of the perceived difficulties with administering its obscenity test.[93] Another may be the risk of error in applying a complex rule, especially when the complex rule needs to be applied by many lower courts or executive officials.

The decisions that position A would require might also prove burdensome if they are seen as too arbitrary or as involving too much second-guessing of others’ judgments. It may at first seem appealing to carve out an exception from a criminal procedure rule for especially serious crimes; but because courts are properly hesitant to disagree with legislative judgments about which crimes are serious, they may ultimately feel compelled to apply the rule to more and more offenses.[94]

Likewise, a rule that legislatures may set prices only when a business is “affected with a public interest” may seem appealing in principle, but it might require judges to make so many contestable and controversial decisions that they may eventually choose to abandon the rule altogether, and give legislatures a free hand.[95] And once a law condemns the display of “pornography,” for instance on the grounds that it constitutes hostile work environment sexual harassment, it becomes likely—in the absence of a precise definition of pornography—that this will be applied to “legitimate art” as well.[96]

Similarly, the broad Free Exercise Clause protection established by Sherbert v. Verner and Wisconsin v. Yoder was developed in cases where the religious claim was a traditional doctrine of well-established religious groups, seen as central to their belief systems, and understood by outsiders as consistent with the groups’ other religious tenets.[97] But over the years, the Court broadened free exercise protection to cover even idiosyncratic, seemingly not fully consistent beliefs, as well as beliefs that many suspect are far from central to people’s religions, partly because it concluded that secular courts couldn’t properly inquire into the religious belief’s centrality and consistency.[98]

Finally, linking this to equality slippery slopes, consider one prominent Dutch doctor’s argument that a decision to seek assisted suicide simply to avoid becoming a burden to one’s family should be treated the same as other assisted suicide decisions: There’s no principled way, the doctor reasoned, to distinguish “that kind of influence—these children wanting the money now” from other influences “from the past that . . . shaped us all,” such as “religion . . . education . . . the kind of family [the person] was raised in, all kinds of influences from the past that we can’t put aside.”[99]

People naturally hesitate to question others’ judgments about what makes their lives worth living or death worth choosing. A rule that a doctor may only assist patients who have certain reasons for suicide may seem defensible in principle, and may seem practicable enough that even those who are skeptical of broader assisted suicide schemes can endorse it. But if the public—or particular professional subgroups, whether doctors or judges—finds these decisions to be unduly disrespectful of patients’ own value systems, then over time this rule may be replaced by a broader deregulation of assisted suicide.

3. The relationship between equality and administration cost slippery slopes and constitutional equality rules

Equal treatment, of course, is sometimes not just a political preference but a constitutional command. If a legislature exempts labor picketing from a residential picketing ban (A), then a court will likely strike down the ban altogether (B), because content-based speech restrictions are presumptively unconstitutional.[100] If a legislature enacts a school choice program limited to secular public and private schools (A), a court might conclude that religious schools must also be covered (B), because of the constitutional ban on discrimination based on religiosity.[101] Some administration costs are likewise seen as unconstitutional, for instance if they require a court to determine which practices are central to a religion’s belief system.[102]

This equal treatment command also flows from multi-peaked preferences, though on the part of judges. The Justices who created the rule, and those who choose to follow it, believe that both 0 (all residential picketing is allowed) and B (all residential picketing is banned) are constitutionally acceptable, but they find A to be the worst position of the three, because they conclude that A is unconstitutionally discriminatory.[103]

Overlaying the multi-peaked judicial preferences with the legislative preferences, which might be single-peaked, then produces the slippery slope. Legislators who prefer A over both 0 and B (a single-peaked preference) may enact decision A, but then an equality rule created by Justices who prefer both 0 and B over A (a multi-peaked preference) commands a shift to result B.[104]

4. Judicial-judicial equality slippery slopes and the extension of precedent

a. Simply following precedent: a legal effect slippery slope

One of the most common “A will lead to B” arguments is an argument that judicial decision A would “set a precedent” for decision B.[105] This generally means that (1) A would rest on some justification J and (2) justification J would also justify B.[106]

Consider, for instance, the debate about whether the government should be allowed to ban racial, sexual, and religious epithets (beyond just those that fit within the existing fighting words and threat exceptions). To uphold such a ban (decision A), the courts would have to give some general justification for why these words should be punishable, essentially creating a new exception to First Amendment protection.

And if the justification J is that “epithets add little to rational political discourse and are thus ‘low-value speech,’ which may be punished,” then courts could equally use this to uphold bans on flagburning, profanity, and sexually themed (but not obscene) speech, all examples of speech that some argue is of “low value” (result B).[107] In fact, a lower court might feel bound to reach result B because of precedent A’s acceptance of justification J. One might call this a legal effect slippery slope, because B follows from A simply as an application of an existing legal rule (the obligation to follow precedent).

A related legal effect slippery slope may arise when the justification underlying A is vague enough that it could justify B, even if this isn’t certain. Thus, say that the Court concludes that campus bans on racial, sexual, and religious slurs are constitutional (decision A) because under a totality-of-the-circumstances balancing test the benefits of allowing the bans outweigh the costs (justification K). Proponents of the decision may say that K wouldn’t justify bans on reasoned arguments about biological differences between the sexes, about the supposed immorality of various religious belief systems, about the supposed failings of various race-based cultures, and so on (result B). But it’s hard to confidently accept this assurance—K is vague enough that future judges could equally well conclude that K does justify or even require B.[108]

Another variant of this argument is the “argument from added authority.”[109] Accepting a decision and its underlying justification, the argument goes, grants extra authority to some decisionmaker. Imagine a proposal to ban all racist advocacy, and not just slurs, justified by the argument that “racist ideas are wrong and therefore aren’t constitutionally protected.”[110] A court that accepts this justification would also be legitimizing the notion that courts have the authority to decide which ideas are wrong and therefore punishable.[111] And once this added authority is accepted, other bad decisions might follow from it: For instance, other judges might use this authority to uphold the suppression of anti-government ideas, anti-war ideas, or Socialist ideas.

So far, the way that A can lead to B is clear: There’s a legal rule that courts should generally follow precedent, and if A sets a precedent that embodies justification J, then lower courts in future cases may feel legally bound to apply J as well. Coordinate courts and the same court would also feel at least presumptively bound to apply J, unless there’s a strong reason for them to reject the precedent.

But this legal effect slippery slope doesn’t by itself provide much of an argument against result A, because advocates of A could simply urge that courts decide A based on a narrower justification that avoids the excessive breadth or the added authority. For instance, someone could argue that bans on racial, sexual, and religious slurs are constitutional because

· only racially, sexually, and religiously bigoted epithets are “low-value speech” and can thus be punished (J1);

· epithets are “low-value speech” and thus may be restricted if a sufficient level of harm is shown—and this level of harm is present for racially, sexually, or religiously bigoted epithets but not for other epithets (J2);

· epithets are “low-value speech,” but the Court has the authority to draw such a conclusion only about epithets, not about more reasoned discourse (J3).

Under each of these justifications, A’s defenders would argue, bad result B would not follow as a direct legal effect. To argue that making judicial decision A will lead to B, one thus needs to rely on more than just an assertion that “A will set a precedent for B.” Defenders of A can always craft some legal justification for A that distinguishes between this result and the unwanted result B.

b. Extension of precedent as an equality / administration costs slippery slope

But that a distinction between A and B can be drawn doesn’t mean that enough future judges will end up being persuaded by this distinction.[112] Even judges who aren’t legally obligated to follow precedent A, because its justification is not literally applicable to current case B, might still feel moved to extend A beyond its original boundaries.

For instance, consider justification J1, which would authorize A (racial epithets are punishable but others are protected) but not B (epithets, bigoted or not, are unprotected). Its supporters believe that racial epithets and other epithets are distinguishable, but some Justices might not be persuaded by the distinction. They may particularly oppose restrictions that they see as viewpoint-based.[113] They may oppose having flagburning, which they see as an anti-American epithet, be more protected than other epithets.[114] Or they might simply conclude that bigoted epithets are not in any relevant way different from other epithets, and believe that their duty to treat like cases alike obligates them to treat all epithets the same way.[115] Those Justices might therefore view A as the least satisfactory position, less appealing than either 0 or B.

Say, then, that the Justices form the following blocs; bloc I and bloc II can have any number of Justices between 1 and 4, so long as they add up to 5:

|

Bloc |

Choice 1 |

Choice 2 |

Choice 3 |

Attitude |

# of Justices |

|

I |

0 |

B |

A |

“More

speech protection is best, but distinguishing bigoted epithets from others is

the worst” |

4/3/2/1 |

|

II |

A |

0 |

B |

“Punishing

only bigoted epithets is best, but if we can’t have that, then protect all epithets” |

1/2/3/4 |

|

III |

B |

A |

0 |

“As much

restriction of epithets as possible” |

4 |

On a Court where the Justices fall into these blocs, a proposal to move directly from “epithets protected” (0) to “all epithets unprotected” (B) would lose 5-4; only bloc III would prefer B over 0. But a proposal to move from 0 to “bigoted epithets unprotected” (A) would win, with the support of blocs II and III. A proposal to move from A to B would then also win, with the support of blocs I and III. And any proposal to then move from B back to 0 would lose, so long as even one Justice’s willingness to adherence to precedent overcomes his substantive preference for 0 over B.

So in our scenario the bloc II Justices were persuaded that bigoted epithets should be treated differently from other epithets; and their arguments may be logically defensible. But in practice, the arguments were not fully persuasive to blocs I and III, and so the bloc II Justices got the worst result from their perspective: Their desire to create an exception for bigoted epithets has led to the denial of protection to all epithets.[116]

Thus, even with no changes to the Court’s personnel, a decision A that doesn’t legally command B (and that some Justices see as consistent with the rejection of B) might still bring B about through the equality slippery slope.[117] And equality slippery slopes may be particularly likely for judges. Judges are expected to explicitly justify their decisions, and to have principled reasons—reasons that make logical sense at least to themselves—for the distinctions they draw;[118] they may therefore be more reluctant than legislators or voters to adopt what they see as logically untenable compromises, which is how the judges in bloc I would view result A.[119]

This sort of slippery slope may have occurred in the evolution of free speech law in the mid-1900s. Consider decision A, the rule that the government may not restrict political advocacy unless the advocacy creates a “clear and present danger” of some serious harm;[120] decision B, the extension of this protection to entertainment rather than just serious political discourse, a step the Court took in the 1948 Winters v. New York decision;[121] and decision C, the extension of this protection to much sexually themed speech, at least so long as the speech falls outside the narrow obscenity exception.[122]

The 6-Justice majority in Winters relied in large part on the unadministrability of any dividing line between political advocacy and entertainment.[123] Likewise, once Winters was decided, the Court eventually held against protecting entertainment related only to topics other than sex, largely because of the felt need to treat ideas—whether about sex or politics—equally.[124] The Winters result was not precedentially required by the clear-and-present-danger cases, and the protection of sexually themed speech was not required by Winters. But the precedents, coupled with the Justices’ concerns about administrability and equality, led to the law we have now, through precedential evolution though not precedential command.

Perhaps some of the Justices who adopted the clear and present danger test in the 1930s and early 1940s would have wanted B and C as well as A. But it’s also possible that they would have been surprised by the eventual slippage, and might have thought twice about supporting A—at least in its pure form, with no qualifying language—had they anticipated this result. In 1942, for instance, the Court still assumed that “lewd,” “profane,” and “obscene” speech was unprotected,[125] and obscenity was at the time defined to include much sexually themed material that’s protected today.[126] As late as 1950, Justice Douglas, who eventually became a solid vote for the protection of sexually themed speech, said that “obscenity and immorality” were “beyond the pale.”[127]

Nor was the slippage from A to B and C just the effect, identified by Fred Schauer, of “linguistic imprecision” and “limited comprehension.”[128] Those Justices who voted for decisions B and C might have agreed that they were going beyond the boundaries that those who rendered decision A would have preferred. But they would still have been willing to go beyond those boundaries, because they preferred B to A, and C to B.

Thus, a judge deciding whether to adopt proposed principle A may worry that future judges, who have their own understandings of equality or administrability that the original judge does not share, might deliberately broaden B. And there’s little that the original judge can do when adopting A to prevent this broadening: For instance, saying “but this decision should not lead to B” in the opinion justifying A won’t be that helpful, since judges who prefer B to A on equality or administrability grounds may not be much swayed by such a statement.

E. Multi-peaked preferences and unconstitutional intermediate positions

Opponents of decriminalizing marijuana sales (A) have sometimes argued that such decriminalization might help lead to legalizing marijuana advertising (B), in which billions would be spent to persuade more people to smoke marijuana.[129] But why would this be so? After all, A and B are clearly logically distinguishable.

The answer lies in the Court’s commercial speech doctrine. Under current First Amendment law, the government may ban commercial advertising of illegal products.[130] But if selling the product becomes legal, prohibiting advertising of the product becomes much harder (though perhaps not impossible).[131] So if selling marijuana is decriminalized, courts may find that marijuana sellers have a constitutional right to advertise.[132]

As with constitutional equality rules (see Part II.D.3 above), this phenomenon arises out of the overlay of legislative preferences, which may be single-peaked, and multi-peaked judicial preferences. The legislature may prefer position A (legalize marijuana sales but keep advertising illegal) over positions 0 (keep marijuana illegal) and B (legalize both sales and advertising). But a majority of the Justices have expressed a different preference: They see 0 and B as constitutional and thus within the legislature’s prerogative, but they believe that position A is at least constitutionally suspect.[133]

Combining the two preferences, and recognizing that the Justices’ constitutional decisions trump the legislature’s choices, we see that if the legislature moves from 0 to A, the Court’s commercial speech jurisprudence—which is a result of the Justices’ multi-peaked preferences—may then move the law from A to B.[134] And again, voters or legislators who are considering whether to support a move from 0 to A should consider the possibility that A will be unstable, because some important group (here judges rather than other voters or legislators) may find A to be inferior to both extreme alternatives.

F. The hidden slippery slope risk and unexpected outcomes exposing multi-peaked preferences

The discussion above has assumed that we know up front the preferences people have among positions 0, A, and B. But sometimes B might not even be discussed at first, and the apparent choice might just be between 0 and A—shall we have marijuana be legal (0) or be subject to mild penalties (A)? Instead of the table

|

Group |

Choice 1 |

Choice 2 |

Choice 3 |

Attitude |

Voting Strength |

|

1 |

0 |

A |

B |

“Restrict drugs as little as possible” |

10% |

|

2 |

0 |

B |

A |

“Restricting drugs is bad, but contempt for the law is

even worse” |

20% |

|

3 |

A |

0 |

B |

“A little restriction is good, but hard-core

enforcement is very bad” |

20% |

|

4 |

A |

B |

0 |

“A little restriction is good, and having no

restriction is very bad” |

10% |

|

5 |

B |

0 |

A |

“Drugs are bad, but contempt for the law is even

worse” |

10% |

|

6 |

B |

A |

0 |

“Drugs are bad, do as much as you can to stop them” |

30% |